TFA Interview Guide on Option Greeks for Quantitative Risk Management And Professional Traders

- Pankaj Maheshwari

- Apr 1

- 19 min read

Updated: Nov 19

Option Greeks form the cornerstone of derivatives risk management, providing traders and risk managers with essential tools to understand, measure, and hedge the complex risks inherent in options portfolios. From the collapse of Barings Bank in 1995 due to unhedged options positions to the "Volmageddon" of 2018 when inverse volatility products imploded, history has shown that misunderstanding or mismanaging Greeks can lead to catastrophic losses even for sophisticated market participants.

This interview reference is designed to prepare you for technical discussions on Option Greeks and their applications in risk management roles at investment banks, proprietary trading firms, market-making operations, and hedge funds. It covers the fundamental mathematical concepts, practical hedging strategies, and real-world considerations that form the foundation of modern derivatives risk management.

The reference is structured around key topics that frequently appear in interviews:

Basic Concepts: Understanding the fundamental nature of Option Greeks, their mathematical foundations, and why they are critical for measuring and managing the multi-dimensional risks in options portfolios. This section establishes the framework for understanding how option prices change in response to various market factors.

What are Option Greeks, and Why are They Important in Risk Management?

Option Delta - The First-Order Price Sensitivity: Delta, the most fundamental Greek that measures an option's price sensitivity to underlying asset movements. This section covers everything from basic interpretation to advanced applications in portfolio hedging, probability estimation, and the nuances of Delta behavior across different market conditions and option types.

What Exactly is Option Delta? What is the Value of Delta for an At-The-Money (ATM) Option, and How Does Delta Behave as the Option Moves In-The-Money or Out-of-The-Money?

How Does Delta Change With Respect to Time to Expiration?

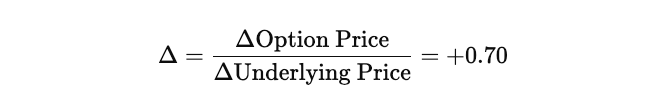

What Does a Delta of +0.7 Signify for a Call Option?

Given That the Delta of a Call Option Is 0.5620, What Would Be the Delta of the Corresponding Put Option?

How Does the Delta Profile of a Long Straddle Differ from that of a Short Straddle?

What happens to the Delta of a Covered Call Position when the Stock Price Moves toward and far from the Strike Price?

How Do You Calculate Delta Using the Black-Scholes Model?

What’s the Relationship Between Delta and Probability? Or, Is Delta the Probability of Expiring ITM?

If You Hold 10 Call Option Contracts (100 Lot Size per Contract) with a Delta of 0.5620, What is the Total Position Delta? Or, How Many Shares of Stock Does This Position Behave Like?

What is Delta-Neutral Hedging? Or, How Can You Offset a Long Call Position with Stock to Eliminate Delta Exposure?

If a Stock Moves From $100 to $110, will a Call Option With an Initial Delta of 0.60 Gain Exactly $6.00?

Why Do Delta-Neutral Portfolios Require Continuous Rebalancing? Or, What Are the Costs and Benefits of Dynamic Hedging?

How Does Implied Volatility Skew Affect Delta? Or, Why Might Two Near ATM Options With Different Strikes Have Different Deltas?

What is "Charm" (Delta Decay) and How Does it Affect Delta Hedging Strategies?

How Do You Manage a Portfolio With Options at Different Strikes and Expiries? And, How Do You Aggregate the Delta Across All Positions?

How Does Delta Behave Differently for American vs European Options?

How would Delta change if you could trade continuously vs. discrete time periods? What are the practical implications?

You have a portfolio that is currently delta-neutral, but you expect high volatility tomorrow due to an earnings announcement. How would Delta considerations affect your strategy?

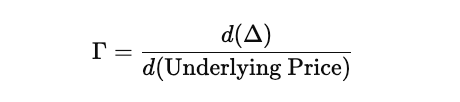

Option Gamma - The Second-Order Sensitivity and Convexity Risk: Understanding Gamma, the rate of change of Delta, which captures the convexity of options and determines how rapidly hedges deteriorate. This section explores why Gamma is crucial for understanding the stability of hedged positions, the risks around at-the-money options, and the challenges of maintaining Delta-neutral portfolios in volatile markets.

What Exactly is Option Gamma? Why is Gamma Highest for At-The-Money (ATM) Options and Lowest for Deep In-The-Money or Out-of-The-Money Options?

How Does Gamma Change With Respect to Time to Expiration? Or, Why is Gamma Risk Particularly Important for Short-Dated Options?

What is the Relationship Between Gamma and Realized vs. Implied Volatility?

How Does the Gamma Profile of a Long Straddle Differ from that of a Short Straddle?

What happens to the Gamma of a Covered Call Position when the Stock Price Moves toward and far from the Strike Price?

How Does Gamma Impact the P&L of a Delta-Hedged Portfolio?

How Do You Hedge Gamma Risk? What are the Trade-offs Between Different Approaches?

Why do Risk Managers monitor Delta and Gamma together in an Options Portfolio?

What is the Difference Between First-Order and Second-Order Greeks? Why Does This Distinction Matter?

Risk Management Applications: Advanced techniques for implementing Greeks-based risk management in practice, including sensitivity-based valuation approaches, computational trade-offs, and the practical considerations of managing large derivatives portfolios. This section bridges the gap between theoretical understanding and real-world application.

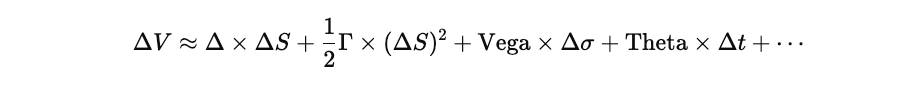

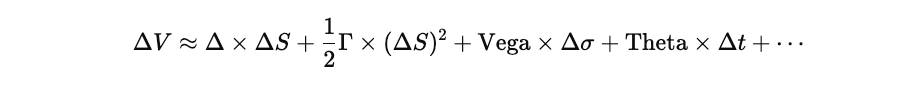

What is the Sensitivity-Based Partial Revaluation Approach, and Why is it used in Risk Management?

What are the Key Assumptions Behind Using the Delta-Gamma-Vega (DGV) Approximation for Risk Estimation?

How Does the Sensitivity-Based Partial Revaluation Approach Differ from Full Revaluation Methods, and What are Its Computational Trade-Offs?

What is "Greeks-Based P&L Explain" and How Do You Perform It?

How Do You Aggregate Greeks Across a Multi-Asset Portfolio?

Each section provides not just mathematical formulations but also practical market context through historical examples, trading floor insights, and regulatory considerations under frameworks like Basel III and FRTB (Fundamental Review of the Trading Book). The questions progress from foundational concepts to advanced technical challenges, reflecting the depth of knowledge expected in quantitative trading and risk management roles.

What are Option Greeks, and Why are They Important in Risk Management?

Option Greeks are sensitivities that measure how an option's price changes in response to different factors, such as the price of the underlying asset, implied volatilities, time, and interest rates.

These sensitivities provide critical insights into the risks associated with an options position (or an options portfolio) and allow traders and risk professionals to hedge their non-linear, multi-factor risk exposures effectively.

The most commonly used Greeks include:

Delta (Δ): It measures the rate of change of the option price to changes in the underlying price.

Gamma (Γ): It measures the rate of change of Delta to changes in the underlying price.

Vega (ν): It measures the rate of change of the option price to changes in implied volatility.

Theta (θ): It measures the rate of change of the option price to time decay.

Rho (ρ): It measures the rate of change of the option price to changes in interest rates.

In sophisticated risk setups, especially involving exotic options, structured products, or large books, risk managers also consider Vanna, Volga, and Charm in risk management strategies.

Manage Directional Risk (Delta):

Delta measures how much an option's price is expected to change for a $1 change in the underlying asset price. It is the first line of defense in managing directional exposure.

It helps risk managers create delta-neutral positions, neutralize small price movements in the underlying (directional risk), thereby isolating other factors like implied volatility or time decay.

A Delta-neutral position ensures that small price movements in the underlying do not impact the portfolio.

For example, a trader short 100 calls with Delta = 0.50 per contract will have a total Delta of -50 (100 x -0.50). To neutralize this exposure, they can buy 50 shares of the underlying asset.

Manage Convexity Risk (Gamma):

Gamma measures how much the option's delta changes for a 1$ change in the underlying price, helping risk managers understand how Delta itself shifts by capturing the curvature of the PnL profile.

High Gamma increases the risk of sudden large moves (delta shifts rapidly), especially at-the-money (ATM) options.

For example, in a Delta-neutral but high-Gamma position, a small move in the underlying asset will require frequent adjustments to maintain the hedge, potentially increasing slippage and transaction costs.

Manage Volatility Risk (Vega):

Vega measures how much an option's price changes for a 1% change in implied volatility (IV).

Option traders use Vega-neutral strategies to isolate movements in the underlying without exposure to volatility shifts and time decay.

It helps risk managers manage volatility risk, essential in event-driven markets or earnings announcements, or macroeconomic events.

For example, a long straddle strategy has high Vega. If implied volatility drops significantly, the strategy could lose value even if the underlying remains near the strike price.

Manage Time Decay (Theta):

Theta measures the rate at which an option loses value as time passes, assuming all else remains constant.

Short options positions (for example, covered calls, short straddles) benefit from positive Theta, while long positions lose value.

For example, an at-the-money (ATM) option has higher Theta decay as expiration approaches. A trader long on this option may need to adjust positions or close out early to avoid losses from time erosion.

Manage Interest Rate Risk (Rho):

Rho measures how much an option's price changes for a 1% change in interest rates.

While its impact is usually minor for short-dated options, it’s more relevant for long-dated options and interest rate-sensitive derivatives.

Also, shifts in interest rates can alter the present value of expected payoffs, especially in structured or fixed-income-linked derivatives.

For example, a trader managing a book of long-term equity options or rate options must monitor Rho to adjust for macro shifts in the yield curve.

What Exactly is Option Delta?

What is the Value of Delta for an At-The-Money (ATM) Option, and How Does Delta Behave as the Option Moves In-The-Money or Out-of-The-Money?

Delta represents the first-order sensitivity of an option’s price to changes in the price of the underlying asset. It measures the rate of change, that how much the option price is expected to move for a $1 change in the underlying asset’s price, with all other factors remaining constant. For example,

A call option with Delta +0.60: If the stock increases by $1, the option is expected to increase by $0.60.

A put option with Delta –0.40: If the stock increases by $1, the option is expected to decrease by $0.40.

Call Options Have Positive Delta (0 to +1): Delta moves in the same direction as the underlying. When the stock rises, call values increase. When the stock falls, call values decrease.

Put Options Have Negative Delta (-1 to 0): Delta moves opposite to the underlying. When the stock rises, put values decrease. When the stock falls, put values increase.

Delta ranges between 0 to +1 for call options (a higher Delta indicates a greater sensitivity to the underlying asset price) and between 0 to -1 for put options (a more negative Delta indicates stronger inverse sensitivity to the underlying asset price).

What is the Value of Delta for an At-the-Money (ATM) Option?

When the strike price is equal (or very close) to the current market price of the underlying, the option is considered At-the-Money (ATM).

Call Delta ≈ +0.50, Put Delta ≈ -0.50

This implies that the price of the option is expected to move approximately 50% of the underlying price movement (moderately sensitive). The exact Delta might be slightly above or below 0.50, depending on:

Time to expiration (shorter time → closer to exactly 0.50)

Interest rates (higher rates → slightly higher Delta)

Dividends (higher dividends → slightly lower Delta)

Volatility (affects the exact value, but ATM Delta remains near 0.50)

How Does Delta Behave Across Moneyness?

In-the-Money (ITM) Options: As options move deep into the money, their probability of expiring in-the-money increases, which makes them behave more like the underlying asset itself. It approaches toward +1 (call option) and -1 (put option).

This reflects a stronger correlation between the option price and the underlying, as the option behaves more like the underlying asset. For example, a deep ITM call option with a Delta of +0.95 will increase by $0.95 for every $1 increase in the underlying price. It behaves almost like owning the stock directly.

Out-of-the-Money (OTM) Options: As options move further out-of-the-money, their likelihood of expiring worthless increases, which reduces their price sensitivity to small changes in the underlying. It approaches 0 for both call and put options.

This reflects the fact that OTM options have a lower chance of expiring in the money, and hence, the option price becomes less sensitive to small changes in the underlying price. For example, an OTM call with a Delta of +0.10 will move only $0.10 for every $1 move in the stock, indicating low price sensitivity.

Relationship Between Delta and Moneyness:

Moneyness | Delta Range | Scenario |

Deep OTM | 0.00 - 0.25 | Flat Curve, Low Sensitivity, Slow Delta Changes |

OTM | 0.25 - 0.45 | Steepening Curve, Increasing Sensitivity |

ATM | 0.45 - 0.55 | Steepest Part of the Curve, Maximum Sensitivity |

ITM | 0.55 - 0.75 | Curve Flattening, High but Stabilized Sensitivity |

Deep ITM | 0.75 - 1.00 | Nearly Flat, Approaching Stock-like Behaviour |

While Delta measures price sensitivity, it is also often interpreted as a proxy for the probability that the option will expire ITM. For example, a call with Delta equal to +0.70 implies a ~70% chance (under Black-Scholes assumptions) that the option will expire ITM.

What’s the Relationship Between Delta and Probability?

Or, Is Delta the Probability of Expiring ITM?

Delta represents the probability that the option will expire ITM. As per the pricing function provided by the Black-Scholes-Merton (BSM) model.

In the Black-Scholes framework, the call option Delta equals N(d₁), where N represents the cumulative standard normal distribution function and d₁ is a specific value calculated from the option's parameters. Here, N(d₁) is the probability that helps in determining the expected payoff in case the option is exercised (or expires in the money) and is called the option's delta. The formula to arrive at this is provided by Black and Scholes in their pricing model.

In fact, this N(d₁) term has a dual interpretation- it is simultaneously the sensitivity of the option price to underlying price changes and the risk-neutral probability that the option will finish ITM at expiration.

This probabilistic interpretation provides powerful intuition for understanding Delta values:

At-the-Money (ATM) options have Delta near 0.50 for calls (-0.50 for puts), reflecting the roughly 50-50 probability that the option will expire in-the-money versus out-of-the-money.

In-the-Money (ITM) or Deep ITM options have Delta near 1.00 for calls (-1.00 for puts), reflecting the high probability (approaching certainty) that these options will expire in-the-money.

Out-of-the-Money (OTM) or Deep OTM options have a Delta near 0.00 for calls and puts, reflecting the low probability that these options will expire in-the-money.

The call option's Delta of 0.5620 suggests this is approximately ATM with roughly 56% probability of expiring ITM. This probabilistic interpretation helps traders understand why Delta changes as markets move. When a stock rallies, call options become more likely to expire ITM, so their Delta increases. On the other hand, put options become less likely to expire ITM, so their Delta (in absolute value) decreases.

The probability interpretation strictly applies to the risk-neutral probability measure used in option pricing theory, not necessarily to actual (physical) probabilities of market outcomes. Nevertheless, it provides valuable intuition for understanding Delta behavior.

What Does a Delta of +0.7 Signify for a Call Option?

A Delta of +0.70 for a call option indicates that the option’s price is expected to increase by $0.70 for every $1.00 increase in the price of the underlying asset, assuming all other factors remain constant (volatility, time to maturity, and interest rates are unchanged).

A Delta of +0.70 typically suggests that the call is in-the-money (ITM) or approaching deep ITM, with a high probability of expiring ITM.

The higher the Delta, the more responsive the option price to the movements in the underlying price, and the less impacted by volatility or time decay. As Delta approaches +1, the option’s behavior closely resembles that of the underlying asset itself.

In risk management, Delta serves as a hedge ratio. If a trader is long by 100 call options, each with a Delta of +0.70, the total Delta exposure would be 100 x 0.70 = +70. This means the portfolio behaves like being long 70 shares of the underlying stock. To hedge or neutralize this directional exposure, the trader would short 70 shares of the underlying, making the overall position Delta-neutral.

Please note that the Delta of +0.70 is not static; it will change with market movements, a property captured by another Greek called Gamma.

Given That the Delta of a Call Option Is 0.5620, What Would Be the Delta of the Corresponding Put Option?

Put-Call Delta Relationship (European Options)

For European-style options (with no dividends), the Delta of a call and the Delta of the corresponding put are related as:

Put Delta = Call Delta - 1, or Δput = Δcall - 1

For non-dividend-paying stocks, this can also be expressed as:

Δcall + |Δput| = 1

(the sum of the absolute values of call delta and put delta equals 1)

Or equivalently: Δcall - Δput = 1

This relationship emerges from put-call parity, one of the fundamental no-arbitrage conditions in options pricing. Put-call parity states that a portfolio containing a long call and a short put (with the same strike and expiration) is equivalent to a forward contract on the underlying asset.

Example:

If the delta of a call option is 0.5620, the delta of a put option is 0.5620 - 1 = -0.4380

It means that if the price of the underlying asset increases by $1, the price of a call option is expected to increase by $0.5620, and that of a put option to decrease by $0.4380.

In absolute terms: |0.5620| + |-0.4380| = 1

This relationship means that |Δ_call| + |Δ_put| = 1 for the same strike. A portfolio consisting of a long call + short put at the same strike behaves like a forward contract with Delta = 1. Therefore, the call Delta minus the put Delta must equal 1.

A Delta of -0.4380 for the put option means: For every $1 increase in the underlying asset’s price, the value of the put decreases by $0.4380. The negative sign indicates the inverse relationship between the price of the underlying and the value of the put option. This also implies that the put option is slightly OTM, since the Delta is greater than -0.5 in magnitude (ATM puts have a Delta ≈ -0.50).

Risk managers use Delta symmetry to cross-check risk exposures across calls and puts. It also helps assess net Delta exposure across long/short portfolios. For example, a portfolio long 100 calls (Δ = +0.5620) and short 100 puts (Δ = –0.4380) has a net Delta of +100.00, behaving as if you're long 100 shares of the stock.

For dividend-paying stocks, this can be expressed as:

Δput = Δcall - exp(-qT)

Where:

q is the continuous dividend yield

T is time to expiration

exp(-qT) is the present value of receiving one unit of the underlying at expiration

The adjustment reflects that owning a stock that pays dividends provides value beyond the capital appreciation captured by Delta. The dividend yield reduces the effective forward price of the stock, which affects the put-call parity relationship.

If You Hold 10 Call Option Contracts (100 Lot Size per Contract) with a Delta of 0.5620, What is the Total Position Delta?

Or, How Many Shares of Stock Does This Position Behave Like?

Position Delta = Number of Contracts x Contract Multiplier (Lot Size) x Delta per Option = 10 x 100 x 0.5620 = 562

This position behaves like owning 562 shares of the underlying stock in terms of directional sensitivity.

If the stock moves up $1: Expected Position Gain = 562 x $1 = $562

If the stock moves down $2: Expected Position Loss = 562 x $2 = $1,124

This is an approximation that works best for small stock moves. For larger moves, Gamma effects mean the actual change will differ from the Delta-based estimate.

What is Delta-Neutral Hedging?

Or, How Can You Offset a Long Call Position with Stock to Eliminate Delta Exposure?

Delta-neutral hedging involves creating a position with total Delta = 0, making the portfolio value insensitive to small moves in the underlying asset.

Example: Initial Position:

Long 20 Call Option Contracts (100 lot size per contract equals 2,000 options)

Delta per Option: 0.58

Position Delta: 2,000 x 0.58 = +1,160

To neutralize this Delta exposure, we need to offset the +1,160 Delta. Since the underlying stock has a Delta = 1.00, we short 1,160 shares:

Options Delta: +1,160

Stock Short Position Delta: -1,160

Net Portfolio Delta: 0

For small stock moves, the portfolio value remains approximately constant:

If the stock rises $1:

Options Gain: 1,160 x $1 = +$1,160

Short Stock Loses: -1,160 x $1 = -$1,160

Net Change: ≈$0

If the stock declines $1:

Options Lose: 1,160 x -$1 = -$1,160

Short Stock Gains: -1,160 x -$1 = +$1,160

Net Change: ≈$0

Delta-neutral positions aren't truly "risk-free"; they remain exposed to Gamma risk (Delta changes), Vega risk (volatility changes), and Theta (time decay).

If a Stock Moves From $100 to $110, will a Call Option With an Initial Delta of 0.60 Gain Exactly $6.00?

No, a call option with an initial delta of 0.60 will not gain exactly $6.00 when the stock moves from $100 to $110. Here's why:

Delta is Not Constant

Delta measures the option's price sensitivity to small changes in the underlying stock price, but it changes as the stock price moves. This phenomenon is captured by gamma, which measures the rate of change of delta.

When the stock rises from $100 to $110:

Initial Delta is 0.60: For the first small move, the option gains approximately $0.60 per $1 stock increase.

Delta Increases as Stock Price Rises: As the stock moves higher, the call option moves deeper in-the-money, and delta approaches 1.

Actual Gain > $6.00: Because delta is increasing throughout the move, the option captures more than just 0.60 × $10

Numerical Example:

At $100: Delta = 0.60

At $105: Delta might be ~0.75

At $110: Delta might be ~0.85

The actual option gain would be closer to $7 to $8 rather than exactly $6, depending on:

Time to expiration (shorter time → closer to exactly 0.50)

Interest rates (higher rates → slightly higher Delta)

Dividends (higher dividends → slightly lower Delta)

Volatility (affects the exact value, but ATM Delta remains near 0.50)

The $6.00 estimate only works for very small stock price movements where delta can be assumed constant. For a $10 move (10% on a $100 stock), gamma effects are significant, and delta will change materially, making the linear approximation inaccurate.

What Exactly is Option Gamma?

Why is Gamma Highest for At-The-Money (ATM) Options and Lowest for Deep In-The-Money or Out-of-The-Money Options?

Gamma is the second-order derivative of the option’s price with respect to the underlying asset. It measures the rate of change of Delta to the change in price of the underlying asset:

In simpler terms, Gamma tells us how quickly Delta will change for a $1 move in the underlying asset. This is especially important in Delta-hedged portfolios, where traders need to know how much their hedge ratio will shift as the market moves.

It is positive for long options (calls and puts) and negative for short options.

A high Gamma represents that Delta is very sensitive to changes in the underlying asset and would require more frequent rebalancing to remain delta-neutral.

A low Gamma represents that Delta is relatively stable, requiring less frequent rebalancing.

Why is Gamma Highest at At-the-Money (ATM)?

Gamma is highest when the underlying price is near the strike price, at-the-money (ATM), the reason being- ATM options are the most sensitive to even small price movements in the underlying asset; a slight move can quickly make the option in-the-money or out-of-the-money, resulting in sharp changes in Delta.

If you graph Gamma vs. underlying price, you get a bell-shaped curve centered at the strike price.

Why Does Gamma Decline for Deep In-the-Money (ITM) and Out-of-the-Money (OTM) Options?

In-the-money (ITM or Deep ITM) options: Delta approaches or is nearly close to +1 for call options or -1 for put options, so further changes in the underlying have very little effect on Delta. The option behaves almost like the underlying asset itself, and Gamma approaches zero.

Out-of-the-money (OTM or Deep OTM) options: Delta approaches or is nearly close to 0. Any changes in the underlying are unlikely to affect the option’s moneyness, especially as the time to expiration shortens. Hence, Gamma is also close to zero.

What is the Sensitivity-Based Partial Revaluation Approach, and Why is it used in Risk Management?

The Sensitivity-Based Partial Revaluation approach is a widely used risk approximation technique that estimates how the value of an options or derivatives portfolio changes in response to small movements in market risk factors. It does so without performing a full revaluation (re-pricing each instrument using complex pricing models like Black-Scholes, binomial trees, or Monte Carlo simulations).

Instead of re-running full pricing models for every scenario or shock, the partial revaluation approach uses pre-calculated risk sensitivities, the Greeks (Delta, Gamma, Vega, etc.), to approximate portfolio-level or instrument-level value changes.

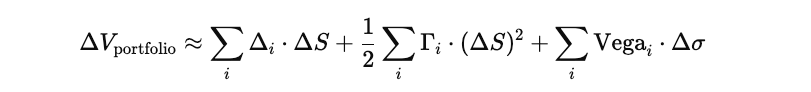

The sensitivity-based partial revaluation approach is based on a Taylor series expansion of the option's value function, truncated at first or second order. The commonly used Delta-Gamma-Vega (DGV) approximation incorporates three primary risk sensitivities:

Higher-order Greeks (Volga, Vanna, Vomma, Charm, etc.) may be included for more precision, especially in portfolios with exotic derivatives, but the DGV approximation often provides sufficient accuracy for risk estimation and decision-making.

Why Is It Used in Risk Management?

Computational Efficiency: In large institutions, portfolios may consist of thousands of options and structured products. Running full revaluation models on every instrument/trade consumes time and computational resources and may be impractical for day-to-day risk management or real-time risk monitoring. Instead, the sensitivity-based partial revaluation approach uses precomputed sensitivities to quickly estimate how portfolio value changes with movements in underlying factors, allowing for fast re-calculation of PnL and risk exposure.

Practical Hedging and Risk Management Insights: Sensi-based partial revaluation doesn’t just save time, it breaks down where the risks lie. By decomposing the risk/portfolio’s exposure into first-order and second-order components, the sensitivity-based approach provides actionable insights into the sources of risk and how to monitor, mitigate, and manage risk exposures effectively:

Delta: Underlying Price → Directional (Linear) Risk → Hedge Using Underlying Asset or Futures.

Delta tells the immediate exposure to price changes and lets traders and risk managers hedge directionally using simple linear instruments.

Gamma: Underlying Price → Directional (Convexity) Risk → Monitor Delta Shifts.

Gamma warns that the Delta hedge will go stale quickly, alerting traders and risk managers to be proactive in volatile markets.

Vega: Implied Volatility → Volatility Risk → Hedge Using Long/Short Vega Instruments.

Vega shows how vulnerable the portfolio is to changes in market uncertainty, which is critical in earnings season, macro events, or stress regimes.

This enables targeted hedging decisions, for example, whether to adjust linear (Delta) or non-linear (Gamma) risk exposure, reduce Vega risk exposure, or reduce non-linear (Gamma) risk in high-volatility environments.

Foundation for Regulatory Capital Models: Under the Basel III enhancements known as the Fundamental Review of the Trading Book (FRTB), regulators now allow, require banks to use sensitivity-based approaches under the Standardized Approach (SA).

These sensitivities are aggregated across risk classes (equity, FX, interest rate, credit, commodities).

Instead of requiring model-specific revaluations, the regulator prescribes risk weights and correlation parameters for sensitivities, thereby reducing dependency on complex full valuation models.

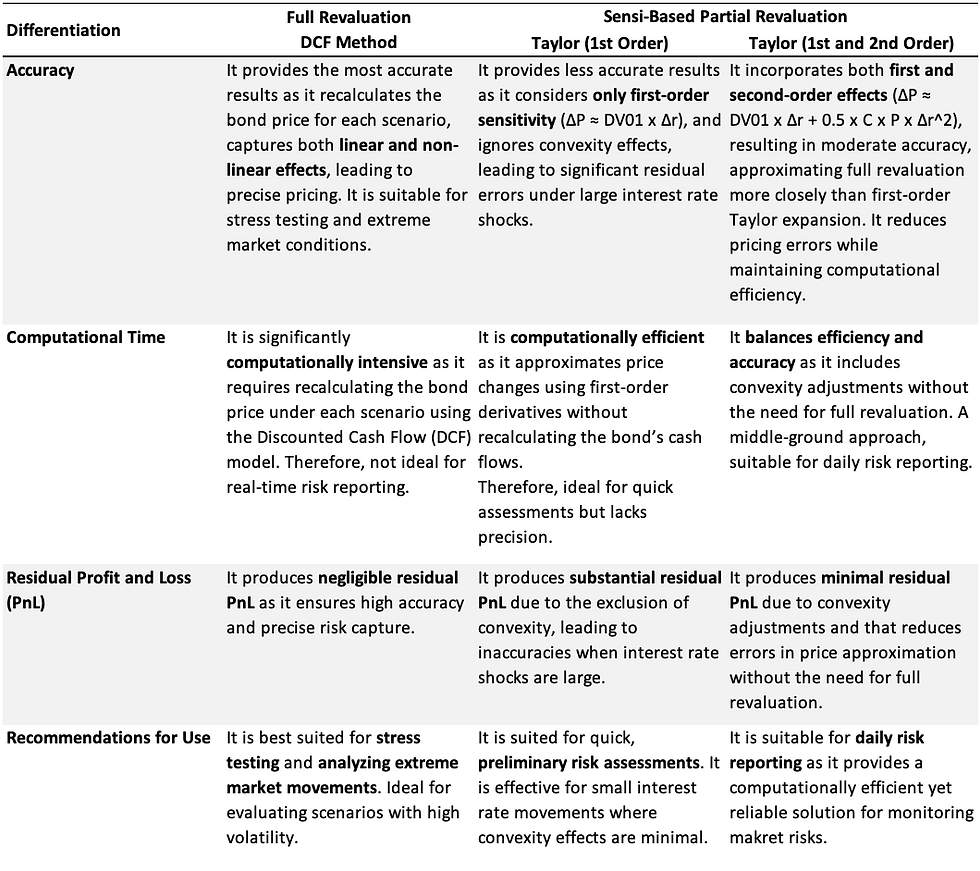

How Does the Sensitivity-Based Partial Revaluation Approach Differ from Full Revaluation Methods, and What are Its Computational Trade-Offs?

The Sensitivity-Based Partial Revaluation approach estimates changes in portfolio value by applying pre-computed sensitivities (Greeks) to shocks in risk factors, rather than re-pricing the entire portfolio using pricing models. This results in a faster but approximate view of risk exposure.

In contrast, Full Revaluation methods re-run the original pricing models (Black-Scholes, binomial trees, or Monte Carlo simulations) with shocked market inputs to obtain the exact change in portfolio value—capturing all non-linear effects and dependencies.

What are the Key Assumptions Behind Using the Delta-Gamma-Vega (DGV) Approximation for Risk Estimation?

The Delta-Gamma-Vega (DGV) approximation is a Taylor series-based method used in sensitivity-based partial revaluation to estimate changes in an option portfolio’s value due to small shocks/changes in key risk factors, primarily the underlying asset price (ΔS) and implied volatility (Δσ).

While this approach is computationally efficient and widely used in regulatory frameworks such as the FRTB Standardized Approach, its effectiveness is contingent on a set of core assumptions. Misalignment with these assumptions can lead to inaccurate risk estimates.

Small Shock Assumption: The DGV method assumes small and incremental changes in market inputs, such as the underlying price (ΔS) and implied volatility (Δσ). The Taylor series expansion used for DGV is valid only in the local neighborhood (±1bp) of the base market scenario.

Limitation: In the event of large or discontinuous market moves, nonlinearities become pronounced, and the approximation becomes unreliable because:

Non-linearities in the option price are not captured beyond the second order.

The error between the approximated and actual price grows rapidly with the size of the shock.

Stability of Sensitivities (Local Linearity): DGV assumes that Delta, Gamma, and Vega remain constant over the shock horizon. These sensitivities are calculated at the current market point and are not recalculated during the simulated market movement.

Limitation: In reality, risk sensitivities (Greeks), especially Gamma and Vega, are functions of the underlying and volatility—can change significantly (Gamma effect) or shift as options move ITM/OTM or approach expiry. This can lead to underestimation or overestimation of risk exposure, especially for non-linear portfolios.

Absence of Higher-Order Greeks: The DGV approximation truncates the Taylor expansion, typically after second or third-order terms. Higher-order Greeks such as Vega’s sensitivity to volatility (Volga), Delta’s sensitivity to volatility (vanna), Charm, Color, Zomma, etc., are ignored.

Limitations: These higher-order sensitivities can be significant in certain portfolios with long-dated options, volatility trading strategies, and exotic derivatives. Ignoring these terms can understate convexity risk or overlook volatility-of-volatility effects, particularly in high-Vega portfolios.

Additivity Across Positions: The DGV framework assumes risk to be linearly additive across trades. The DGV approximates the total portfolio change as the sum of individual position sensitivities:

Limitations: In structured portfolios, options can have payout correlations (dependent on multiple underlying assets), offsetting Greeks, or non-linear interaction effects. Additivity fails when cross-effects, non-linear combinations, or path-dependent exposures exist, leading to underestimated portfolio risk.

No Path Dependency or Early Exercise Features: The DGV approximation assumes no path dependency; the value of the instrument depends only on the current state, not on the path taken to get there. It also assumes no early exercise features, making it best suited for European-style options.

Limitations: The method is not appropriate for instruments with American options (can be exercised before expiry), barrier options (triggered by path), lookbacks, Asians, or digital options. These instruments have non-smooth payoff structures, requiring simulation-based or full revaluation tree-based pricing models for reliable risk estimation.

Comments